Periodontal disease

Highlights

Symptoms of Periodontal Disease

Symptoms of periodontal disease include red and swollen gums, persistent bad breath, and receding gums and loose teeth. Smoking, certain illnesses (such as diabetes), older age, and other factors increase the risk for periodontal disease. If you have periodontal disease, your dentist may refer you to a periodontist, a dentist who specializes in treating this condition. Without proper treatment, periodontal disease can lead to tooth loss, and it has been linked to an increased risk of heart attack and stroke.

Prevent Periodontal Disease: Practice Good Dental Hygiene

Consistent good dental hygiene can help prevent gingivitis and periodontitis. The American Dental Association recommends that everyone:

- Brush twice daily with a fluoride toothpaste (be sure to replace toothbrushes every 1 - 3 months).

- Clean between the teeth with floss or an interdental cleaner.

- Eat a well-balanced diet and limit between meal snacks.

- Have regular visits with a dentist for teeth cleaning and oral examinations.

Treatment

Scaling and root planning is the first approach for treating periodontal disease. This procedure is a deep cleaning to remove bacterial plaque and calculus (tartar). Scaling involves scraping tartar from above and below the gum line. Root planning smoothes the root surfaces of the teeth. Your dentist will reevaluate the success of this treatment in follow-up visits. If deep periodontal pockets and infection remain, periodontal surgery may be recommended.

Periodontal Disease and Heart Disease

Periodontal disease and heart disease are both inflammatory conditions. There appears to be an association between periodontal disease and heart disease, but it is not yet clear if having one condition increases the risk of developing the other. Periodontists and cardiologists recommend that:

- Patients who have periodontal disease and at least one risk factor for heart disease should have a medical evaluation for heart problems.

- Patients who have heart disease should have regular exams to check for signs of periodontal disease.

Introduction

The word “periodontal” means “around the tooth.” Periodontal disease is a chronic inflammatory disease of the gum and tissues that surround and support the teeth. If left untreated, periodontal disease can lead to tooth loss.

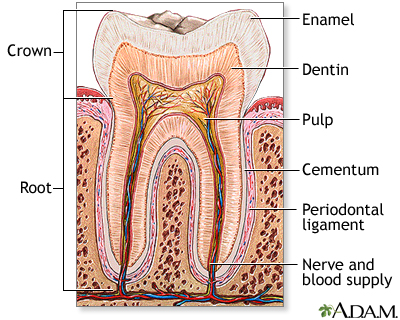

The Periodontium

The part of the mouth that consists of the gum and supporting structures is called the periodontium. It is made up of the following parts:

- Gum (gingiva). When healthy, the gingiva is pale pink, firm, and does not move. It has a smooth or speckled texture. The gingival tissue between teeth is shaped like a wedge.

- The space between the gum and tooth, called the sulcus. The sulcus is the main place where periodontal problems begin.

- Root surface of the teeth (the cementum)

- Connective tissue

- Alveolar bone. The alveolar bone contains the teeth sockets and supports the teeth.

Periodontal Disease

Periodontal diseases are generally divided into two groups:

- Gingivitis, which causes lesions (inflammatory abnormalities) that affect the gums

- Periodontitis, which damages the bone and connective tissue that support the teeth

Periodontal disease is caused by bacteria. Even in healthy mouths, the sulcus is teeming with bacteria, but they tend to be harmless varieties. Periodontal disease usually develops because of two events in the oral cavity: an increase in bacteria quantity and a change in balance of bacterial types from harmless to disease-causing bacteria. These harmful bacteria increase in mass and thickness until they form a sticky film called plaque.

In healthy mouths, plaque actually provides some barrier against outside bacterial invasion. When it accumulates to excessive levels, however, bacterial plaque sticks to the surfaces of the teeth and adjacent gums and causes infection, with subsequent swelling, redness, and warmth.

When plaque is allowed to remain in the periodontal area, it transforms into calculus (commonly known as tartar). This material has a rock-like consistency and grabs onto the tooth surface. It is much more difficult to remove than plaque, which is a soft mass.

Gingivitis

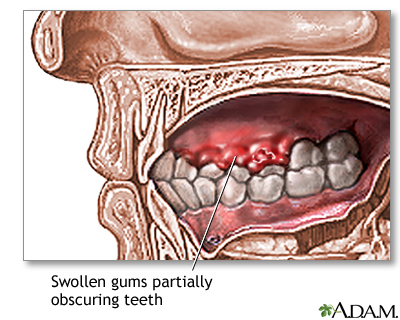

Gingivitis is an inflammation of the gingiva, or gums. It is characterized by tender, red, swollen gums that bleed easily and may be responsible for bad breath (halitosis) in some cases. Gingivitis can be treated by good dental hygiene, proper diet, and stopping smoking. Untreated gingivitis can lead to periodontitis.

Periodontitis

Periodontitis occurs when the gum tissues separate from the tooth and sulcus, forming periodontal pockets. Periodontitis is characterized by:

- Gum inflammation, with redness and bleeding

- Deep pockets (greater than 3 mm in depth) that form between the gum and the tooth

- Loose teeth, caused by loss of connective tissue structures and bone

There are different forms of periodontal disease. They include:

Chronic Periodontitis. Chronic periodontitis is the most common type of periodontitis. It can begin in adolescence but the disease usually does not become clinically significant until people reach their mid-30s.

Aggressive Periodontitis. Aggressive periodontitis is a subtype of chronic periodontitis that can occur as early as childhood. It can lead to severe bone loss by the time patients reach their early 20s.

Disease-Related Periodontitis. Periodontitis can also be associated with a number of systemic diseases, including type 1 diabetes, Down syndrome, AIDS, and several rare disorders of white blood cells.

Necrotizing Periodontal Disease. Necrotizing periodontal disease is an uncommon acute infection of the gum tissue. It is characterized by painful and bleeding gums, bad breath, and rapid onset of pain. If left untreated, necrotizing periodontal disease can spread throughout the facial areas (cheeks, jaw) and cause extensive damage. Necrotizing periodontal disease is usually associated with systemic health conditions such as HIV or malnutrition.

Risk Factors

More than 75% of American adults have some form of gum disease but most are unaware of it. Risk factors for periodontal disease include:

Oral Health

Oral Hygiene. Lack of oral hygiene, such as not brushing or flossing regularly, encourages bacterial buildup and plaque formation.

Sugar and Acid. The bacteria that cause periodontal disease thrive in acidic environments. Eating sugars and other foods that increase the acidity in the mouth increase bacterial counts.

Poorly Contoured Restorations. Poorly contoured restorations (fillings or crowns) that provide traps for debris and plaque can also contribute to periodontitis.

Anatomical Tooth Abnormalities. Abnormal tooth structure can increase the risk of periodontal disease.

Wisdom Teeth. Wisdom teeth, also called third molars, can be a major breeding ground for the bacteria that cause periodontal disease. In fact, for patients in their 20s, periodontal disease is most likely to occur around the wisdom teeth. Periodontitis can occur in wisdom teeth that have broken through the gum as well as teeth that are impacted (buried). Adolescents and young adults with wisdom teeth should have a dentist check for signs of periodontal disease.

Age

While gingivitis is nearly universal among children and adolescents, periodontitis typically occurs as people get older and is most common after age 35.

Female Hormones

Female hormones affect the gums, and women are particularly susceptible to periodontal problems. Hormone-influenced gingivitis appears in some adolescents, in some pregnant women, and is occasionally a side effect of birth control medication.

Menstruation. Gingivitis may flare up in some women a few days before they menstruate, when progesterone levels are high. Gum inflammation may also occur during ovulation. Progesterone dilates blood vessels causing inflammation, and blocks the repair of collagen, the structural protein that supports the gums.

Pregnancy. Hormonal changes during pregnancy can aggravate existing gingivitis, which typically worsens around the second month and reaches a peak in the eighth month. Pregnancy does not cause gum disease, and simple preventive oral hygiene can help maintain healthy gums. Any pregnancy-related gingivitis usually resolves within a few months of delivery. Because periodontal disease may increase the risk for low-weight infants and cause other complications, it is important for pregnant women to see a dentist.

Menopause. Estrogen deficiency after menopause reduces bone mineral density, which can lead to bone loss. Bone loss is associated with both periodontal disease and osteoporosis (loss of bone density).

Family and Personal Factors

Family History. Periodontal disease often occurs in members of the same family. Genetic factors may play a role.

Intimacy. It may be possible to pass the bacteria that causes periodontal disease to others through saliva.

Lifestyle Factors

Smoking. Smoking is the single major preventable risk factor for periodontal disease. Smoking can cause bone loss and gum recession even in the absence of periodontal disease. The risk of periodontal disease increases with the number of cigarettes smoked per day. Smoking cigars and pipes carries the same risks as smoking cigarettes.

Substance Abuse. Long-term abuse of alcohol and certain types of illegal drugs (amphetamines) can damage gums and teeth.

Diet. A healthy diet, including eating fruits and vegetables rich in vitamin C, is important for good oral health. Malnutrition is a risk factor for periodontal disease.

Stress. Psychological stress can cause the body to release inflammatory hormones, which may trigger or worsen periodontal disease.

Medical Conditions Associated with Periodontal Disease

Diabetes. There is an association between diabetes (both type 1 and 2) and periodontal disease. Diabetes causes changes in blood vessels, and high levels of specific inflammatory chemicals such as interleukins, that significantly increase the chances of developing periodontal disease.

Heart Disease. There appears to be an association between periodontal disease and heart disease, but it is not yet clear if having one condition increases the risk for developing the other (see Complications section of this report).

Other Medical Conditions. A number of medical conditions can increase the risk of developing gingivitis and periodontal disease. They include conditions that affect the immune system such as HIV/AIDS, leukemia, and possibly autoimmune disorders (Crohn's disease, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus erythematosus).

Prescription Medications. Gingival overgrowth can be a side effect of many different drugs, most commonly phenytoin (Dilantin, generic), cyclosporine (Sandimmune, generic), and a short-acting form of the calcium channel blocker nifedipine (Procardia, generic).

There have been a few reports of osteonecrosis (bone destruction) of the jaw in patients who take oral bisphosphonate drugs such as alendronate (Fosamax, generic). These drugs are used to treat and prevent osteoporosis. However, almost all cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw associated with bisphosphonate drugs have occurred during or after the use of intravenous bisphosphonates, which are usually given to treat bone cancer or other cancers that have spread to the bone. Symptoms of osteonecrosis of the jaw include loose teeth, exposed jawbone, pain or swelling in the jaw, gum infections, and poor healing of the gums.

As a precaution, the American Dental Association (ADA) recommends that patients who are prescribed or are to receive bisphosphonate drugs get a thorough dental exam before beginning drug therapy, or as soon as possible after beginning therapy. The ADA also recommends that patients who take oral (pill form) bisphosphonate drugs should discuss with their dentists any potential risks from dental procedures (such as extractions and implants) that involve the jawbone. In any case, be sure to inform your dentist if you are taking any type of bisphosphonate drug. Your dentist or oral surgeon may need to take special precautions when performing dental surgery.

Complications

Effect on Heart Disease

Researchers are studying the association between periodontal disease and heart disease. An inflammatory response, which occurs in both periodontal disease and heart disease, may be the common element. Some studies have reported that people who have severe periodontal disease have an increased risk for heart disease and stroke.

However, it is still not clear if periodontal disease actually causes heart disease. Periodontal disease may be a marker of risk for heart conditions rather than a direct risk factor. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force does not currently recommend using periodontal disease as a way to determine a healthy person’s risk of developing heart disease.

It is also not clear if treating gum disease can reduce the risks of heart disease and improve health outcomes for patients with periodontal disease and vascular heart problems. Studies have been mixed, but research is ongoing.

Cardiologists and periodontists currently encourage each other to monitor both conditions in their patients. Periodontists recommend that patients who have periodontal disease and at least one risk factor for heart disease have an annual medical exam to check their heart health. Cardiologists suggest that patients with atherosclerosis and heart disease have regular periodontal exams.

[For more information, see In-Depth Report #03: Coronary artery disease.]

Effect on Diabetes

Diabetes is not only a risk factor for periodontal disease. Periodontal disease itself can worsen diabetes and make it more difficult to control blood sugar.

Effect on Respiratory Disease

Bacteria that reproduce in the mouth can also be carried into the airways in the throat and lungs, increasing the risks for respiratory diseases and worsening chronic lung conditions, such as emphysema.

Effect on Pregnancy

Bacterial infections that cause moderate-to-severe periodontal disease in pregnant women can increase the risk for premature delivery and low birth weight infants. The more severe the infection, the greater the risk to the baby. Research indicates that bacteria from gum disease and tooth decay may trigger the same factors in the immune system that cause premature dilation and contractions.

Women should have a periodontal examination before becoming pregnant or as soon as possible thereafter. Because women with diabetes are at higher risk for periodontal disease, it is especially important that they see a dentist early in pregnancy. Doctors are still not sure if treating periodontal disease can improve birth outcomes. In any case, periodontal treatment is safe for pregnant women.

Symptoms

Symptoms or periodontal disease typically progress over time and include:

- Red and Swollen Gums

- Gum Bleeding. Bleeding of the gums, even during brushing, is a sign of inflammation and the major marker of periodontal disease.

- Bad Breath. Debris and bacteria can cause a bad taste in the mouth and persistent bad breath.

- Gum Recession and Loose Teeth. As the disease advances, the gums recede, and the supporting structure of bone is lost. Teeth loosen, sometimes causing a change in the way the upper and lower teeth fit together when biting down or how partial dentures fit.

- Abscesses. Deepening periodontal pockets between the gums and bone can become blocked by tartar or food particles. Infection-fighting white blood cells become trapped and die. Pus forms, and an abscess develops. Abscesses can destroy both gum and tooth tissue, cause nearby teeth to become loose and painful, and may cause fever and swollen lymph nodes.

Pain is usually not a symptom, which partly explains why the disease may become advanced before treatment is sought and why some patients avoid treatment even after periodontitis is diagnosed.

Diagnosis

The dental practitioner typically performs a number of procedures during a routine dental exam to check for periodontal disease. If periodontal disease is suspected, your dentist may refer you to see a periodontist. A periodontist is a dentist who specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of periodontal disease.

Medical History

The dentist will first take a medical history to reveal any past or present periodontal problems, any underlying diseases that might be contributing to the problem, and any medications the patient is taking. The dentist will also ask questions about the patient’s daily oral hygiene regimen (brushing, flossing).

Oral Examination

Inspection of the Gum Area. The dentist inspects the color and shape of gingival tissue on the cheek (buccal) side and the tongue (lingual) side of every tooth. Redness, puffiness, and bleeding upon probing indicate inflammation and possible periodontal disease.

Periodontal Screening and Recording (PSR). PSR is a painless procedure used to measure and determine the severity of periodontal disease:

- The dentist uses a mirror and a periodontal probe, a fine instrument calibrated in millimeters (mm), which is used to measure pocket depth.

- The probe is held along the length of the tooth with the tip placed in the pocket. The tip of the probe will then touch the point where the connective tissue attaches to the tooth.

- The dentist will "walk" the probe to six specified points on each tooth, three on the buccal (cheek) and three on the lingual (tongue) sides. The dentist measures the depth of the probe at each point.

- Pocket depths greater than 3 mm indicate disease.

These measurements help determine the condition of the connective tissue and amount of gingival overgrowth or recession.

Testing Tooth Movement. Tooth mobility is determined by pushing each tooth between two instrument handles and observing any movement. Mobility is a strong indicator of bone support loss.

X-rays. X-rays are taken to show any loss of bone structure supporting the teeth.

Treatment

According to the American Academy of Periodontology, treatment for periodontal disease should focus on achieving oral health in the least invasive and most cost-effective manner. Your dentist or periodontist will usually begin with a non-surgical approach (scaling and root planning), then reevaluate your condition in follow-up visits. If infection or deep periodontal pockets remain, surgical treatment may be recommended.

Periodontal treatment approaches can basically be categorized as:

- Nonsurgical Approaches. Scaling and root planning (deep cleaning of tartar and bacteria from gum line and tooth root surfaces), which may include the use of topical or systemic antibiotics.

- Surgical Approaches. Periodontal surgical techniques include flap surgery (periodontal pocket reduction), gum grafts, bone grafts, and guided tissue regeneration.

- Restorative Procedures. Crown lengthening is an example of a restorative procedure that may be performed for cosmetic reasons or to improve function. For patients who have already lost teeth to advanced periodontitis, dental implants are another option.

In addition to treatment in a dentist office, regular dental visits and cleanings (usually every 3 months) are important for maintenance as is practicing good oral hygiene at home (see Prevention section of this report).

Non-Surgical Treatment

Scaling and Root Planing. Scaling and root planning is a deep cleaning to remove bacterial plaque and calculus (tartar). It is the cornerstone of periodontal disease treatment and the first procedure a dentist will use. Scaling involves scraping tartar from above and below the gum line. Root planning smoothes the root surfaces of the teeth.

The dentist may apply a topical anesthetic to numb the area before beginning the procedure. Both ultrasonic and manual instruments are used to remove calculus. The ultrasonic device vibrates at a high frequency and helps loosen and remove tartar. A high-pressure water spray is then used to flush out the debris. The dentist will use manual instruments called scrapers and curettes to scrape away any remaining plaque or calculus and smooth and clean the tooth crown and root surfaces. Finally, the dentist will polish the tooth using abrasive paste applied to a vibrating instrument with a rubber cap. Polishing produces a smooth surface, making it temporarily harder for plaque to adhere.

Antibiotics. At the time of scaling and root planning, your dentist may recommend the use of antibiotic medications. Because of the risk of developing antibiotic-resistant infections, antibiotics are recommended only when necessary (for example, in cases of severe active infection). Antibiotics for periodontal disease come in various forms. They may be taken as a prescription mouthwash rinse, or placed topically as dissolving gels, threads, or microchips into the periodontal pockets. In some cases, the dentist may prescribe a short course of systemic antibiotics in a low-dose of doxycycline taken in pill form.

Surgical Treatment

Flap Surgery (Periodontal Pocket Reduction). Surgery allows access for deep cleaning of the root surface, removal of diseased tissue, and repositioning and shaping of the bones, gum, and tissues supporting the teeth. The basic procedure is known as flap surgery. It is performed under local anesthesia and involves:

- The periodontist makes an incision and folds back the gum surface away from the tooth and surrounding bone.

- The diseased root surfaces are cleaned and curetted (scraped) to remove deposits.

- Gum tissue is sewn back into a position to minimize pocket depth. The gum is covered with gauze to soak up any blood.

- The periodontist may also contour the remaining bone or attempt to regenerate lost bone and gingival attachment through bone grafts or guided tissue regeneration.

For several days following surgery, patients should rinse their mouths with warm salt water to help reduce swelling. Gauze pads should be changed. Post-surgical discomfort is usually treated with over-the-counter medications such as ibuprofen or the application of ice packs.

Gum Graft. In cases of excessive gingival recession, the periodontist may perform a gum (gingival) graft to cover the area of exposed root. There are various ways to perform the tissue graft. With a free gingival graft, a thin layer of tissue is removed from the palate of the mouth and sutured onto the exposed root surface. However, many patients find the healing of the donor site on the roof of the mouth to be more painful than the actual surgical procedure. An alternative method, called a subepithelial connective tissue graft, removes tissue from inside the palate (as opposed to the outside, as with the free gingival graft). Recovery is less painful with this method.

An alternative to using tissue from the patient is to use a graft derived from donor (cadaver) tissue. A synthetic graft has also been developed, but it is not yet clear if results are as successful as with the other graft methods.

Bone Graft. In some cases of severe bone loss, the surgeon may attempt to encourage regrowth and restoration of bone tissue that has been lost through the disease process. This involves bone grafting:

- The surgeon places bone graft material into the defect.

- The material may come from the patient (autogenous), from a cadaver (allograft), or from an animal such as a cow (xenograft). An autogenous graft is considered the best approach.

- The gum is then sewn back into place.

- During the next 6 - 9 months, the bone regrows in the jaw area helping to reattach the teeth to the jaw.

Guided tissue regeneration is a more advanced technique that may be used along with bone grafting:

- A specialized piece of fabric called a barrier membrane is placed between the gum and the existing bone.

- The gum is then sewn over the fabric. The fabric prevents the gum tissue from growing down into the bone and allows the bone and the attachment to the root to regenerate.

Restorative and Cosmetic Treatments

Crown Lengthening. Crown lengthening is a surgical procedure performed to expose more of the tooth. It involves readjusting the gum and bone levels by removing small sections of bone and resewing the gums into a new position to allow more tooth exposure.

Dental Implants. For patients who have lost teeth to periodontal disease, dental implants are an option, although an expensive one. Dental implants are an artificial type of tooth root used to create permanent prosthetic teeth. Implants are screws placed into the jawbone. Prosthetic teeth are attached to the implant.

Prevention

In addition to regular visits to a dentist, the best prevention for periodontal disease takes place at home. Healthy habits and good oral hygiene, including daily brushing and flossing, are critical in preventing gum disease and maintaining good oral health after periodontal treatment.

Tooth Brushing

Correct tooth brushing is the first defense against periodontal disease. Here are some tips for making sure you brush correctly:

- Use a soft-bristled brush that fits the size and shape of your mouth. Place the brush where the gum meets the tooth, with bristles resting along each tooth at a 45-degree angle.

- Place the brush where the gum meets the tooth, with bristles resting along each tooth at a 45-degree angle.

- Move the brush back and forth gently. Use short (tooth-wide) strokes.

- Begin by brushing the outer tooth surfaces, followed by the inner tooth surfaces, and then the chewing surfaces of the teeth.

- For the inside surfaces of the front teeth, gently use the tip of the brush in an up-and-down stroke.

- Brush your tongue to help remove additional bacteria.

- Flossing should finish the process. A mouthwash may also be used.

If brushing after each meal is not possible, rinsing the mouth with water after eating can reduce bacteria by 30%.

Toothbrushes. A vast assortment of brushes of varying sizes and shapes are available, and each manufacturer makes its claim for the benefits of a particular brush. Look for the American Dental Association (ADA) seal on both electric and regular brushes.

Electric toothbrushes, particularly those with a stationary grip and revolving tufts of bristles, can be helpful, especially for people with physical disabilities. However, in general, studies have reported no major differences between electric and manual toothbrushes in their ability to remove plaque. If a regular toothbrush works, it isn't necessary to buy an expensive electric one.

The most important factor in buying any toothbrush, electric or manual, is to choose one with a soft head. Soft bristles get into crevices easier and do not irritate the gums, thereby reducing the risk of exposing teeth below the gum line compared to hard brushes.

Be sure to rinse your toothbrush with water after each use. Toothbrushes should be replaced every 1 - 3 months. Worn bristles are less effective at removing plaque, and old toothbrushes may become breeding grounds for bacteria. To prevent the spread of infection, never share toothbrushes.

Flossing

The use of dental floss, either waxed or unwaxed, is critical in cleaning between the teeth where the toothbrush bristles cannot reach. To floss correctly:

- Break off about 18 inches of floss and wind most of it around the middle finger of one hand and the rest around the other middle finger.

- Hold the floss between the thumbs and forefingers and gently guide and rub it back and forth between the teeth.

- When it reaches the gum line, the floss should be curved around each tooth and slid gently back and forth against the gum.

- Finally, rub gently up and down against the tooth. Repeat with each tooth, including the outside of the back teeth.

Here are some tips in choosing the right floss or flossing device:

- Use a floss that does not shred or break.

- Avoid a very thin floss, which can cut the gum if brought down with too much force or not guided along the side of the tooth.

- A floss threader may be helpful for people who have bridgework. Made of plastic, it looks like a needle with a huge eye, or loop. A piece of floss is threaded into the loop, which can then be inserted between the bridge and the gum. The floss that is carried through with it can then be used to clean underneath the false tooth or teeth and along the sides of the abutting teeth.

- Another handy device for cleaning under bridges is a Proxabrush, which is an interdental cleaner. This is a tiny narrow brush that can be worked in between the natural teeth and around the attached false tooth or teeth.

- Special toothpicks such as Stim-U-Dent may be used for wide spaces between teeth but should never replace flossing. Standard toothpicks should never be used for regular hygiene.

- Electric water piks may also be helpful.

Toothpastes and Mouthwashes

Toothpaste. Toothpastes are a combination of abrasives, binders, colors, detergents, flavors, fluoride, humectants, preservatives, and artificial sweeteners. Avoid highly abrasive toothpastes, especially if your gums have receded. The objective of a good toothpaste is to reduce the development of plaque and eliminate periodontal-causing bacteria without destroying the organisms that are important for a healthy mouth.

Ingredients contained in toothpastes may include:

- Fluoride. Most commercial toothpastes contain fluoride, which both strengthens tooth enamel against decay and enhances remineralization of the enamel. Fluoride also inhibits acid-loving bacteria, especially after eating, when the mouth is more acidic. This antibacterial activity may help control plaque.

- Triclosan. Triclosan is an anti-bacterial substance that may help reduce mild gingivitis.

- Metal salts. Metal salts, such as stannous and zinc, serve as anti-bacterial substances in toothpastes. Stannous fluoride gel toothpastes do not reduce plaque, even though they have some effect against the bacteria that cause it, but slightly reduce gingivitis.

- Peroxide and baking soda. Toothpastes with these ingredients claim to have a whitening action, but while they may help remove stains there is little evidence they whiten the actual color of the teeth. In addition, these substances appear to offer no benefits against gum disease.

- Antibacterial sugar substitutes (xylitol), and detergents (delmopinol)

Mouthwash. The American Dental Association recommends (in addition to daily brushing and flossing) antimicrobial mouthwash to help prevent and reduce plaque and gingivitis, and fluoride mouthwashes to help provide additional protection against tooth decay.

- Chlorhexidine (Peridex or PerioGard) is an antimicrobial mouthwash available by prescription to help reduce plaque and prevent gingivitis. Patients should rinse for 1 minute twice daily. They should wait at least 30 minutes (and preferably 2 hours) between brushing and rinsing since chlorhexidine can be inactivated by certain compounds in toothpastes. It has a bitter taste. It also binds to tannins, which are in tea, coffee, and red wine, so it has tendency to stain teeth in people who drink these beverages. Studies are mixed as to its effectiveness for preventing or reducing periodontal disease.

- Listerine is another antimicrobial mouthwash. Generic equivalents are available. It is composed of essential oils and is available over the counter. It reduces plaque and gingivitis, when used for 30 seconds twice a day. It leaves a burning sensation in the mouth that most people better tolerate after a few days of use. The usual regimen is to rinse twice a day. (Listerine PocketPaks, which are strips that dissolve on the tongue, have no proven effects on plaque and gingivitis.)

- Mouthwashes containing cetylpyridinium (Scope, Cepacol, generics) have moderate antimicrobial effect on plaque, but only if they are used an hour after brushing. None are as effective as Listerine or chlorhexidine, but they may still have some value for people who cannot tolerate the other mouthwashes.

- Mouthwashes containing stannous fluoride and amine fluoride (Meridol) are moderately effective, but are also not as effective as effective as Listerine or chlorhexidine.

- Fluoride mouthwashes (Act and generics) are helpful in preventing cavities.

- Mouthwashes that contain alcohol are dangerous for children and should be kept away from them.

Lifestyle Changes

Diet. A well-balanced and nutritious diet is important for good oral health. Limit between-meal snacks and be sure to brush and floss after every meal. It is also important to drink lots of water to help increase saliva and flush away plaque.

Quitting Smoking. Smoking is a main risk factor for periodontal disease. For smokers, quitting is one of the most important steps toward regaining periodontal health.

Resources

- www.nidcr.nih.gov -- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research

- www.perio.org -- American Academy of Periodontology

- www.ada.org -- American Dental Association

- www.aaoms.org -- American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons

References

Amaliya, Timmerman MF, Abbas F, Loos BG, Van der Weijden GA, Van Winkelhoff AJ, et al. Java project on periodontal diseases: the relationship between vitamin C and the severity of periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2007 Apr;34(4):299-304.

Boggess KA; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Publications Committee. Maternal oral health in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Apr;111(4):976-86.

Eberhard J, Jepsen S, Jervøe-Storm PM, Needleman I, Worthington HV. Full-mouth disinfection for the treatment of adult chronic periodontitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Jan 23;(1):CD004622.

Eberhard J, Jervøe-Storm PM, Needleman I, Worthington H, Jepsen S. Full-mouth treatment concepts for chronic periodontitis: a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2008 Jul;35(7):591-604. Epub 2008 May 21.

Friedewald VE, Kornman KS, Beck JD, Genco R, Goldfine A, Libby P, et al. The American Journal of Cardiology and Journal of Periodontology Editors' Consensus: periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2009 Jul 1;104(1):59-68.

Kolahi J, Soolari A. Rinsing with chlorhexidine gluconate solution after brushing and flossing teeth: a systematic review of effectiveness. Quintessence Int. 2006 Sep;37(8):605-12.

Lamster IB, DePaola DP, Oppermann RV, Papapanou PN, Wilder RS. The relationship of periodontal disease to diseases and disorders at distant sites: communication to health care professionals and patients. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008 Oct;139(10):1389-97.

Lamster IB, Lalla E, Borgnakke WS, Taylor GW. The relationship between oral health and diabetes mellitus. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008 Oct;139 Suppl:19S-24S.

Nguyen DH, Martin JT. Common dental infections in the primary care setting. Am Fam Physician. 2008 Mar 15;77(6):797-802.

Persson GR, Yeates J, Persson RE, Hirschi-Imfeld R, Weibel M, Kiyak HA. The impact of a low-frequency chlorhexidine rinsing schedule on the subgingival microbiota (the TEETH clinical trial). J Periodontol. 2007 Sep;78(9):1751-8.

Polyzos NP, Polyzos IP, Mauri D, Tzioras S, Tsappi M, Cortinovis I, et al. Effect of periodontal disease treatment during pregnancy on preterm birth incidence: a metaanalysis of randomized trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Mar;200(3):225-32.

Taylor GW, Borgnakke WS. Periodontal disease: associations with diabetes, glycemic control and complications. Oral Dis. 2008 Apr;14(3):191-203.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Using nontraditional risk factors in coronary heart disease risk assessment: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Oct 6;151(7):474-82.

|

Review Date:

2/7/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |